One expat shares her account of what it's like to teach English in Russia.

I have taught English in Moscow for a year now, and overall I’ve had a hugely positive experience. The job was stimulating, my school supportive, and I avoided the infamous Russian mafia people all warn you about before you come. Of course it wasn’t all positive – so here is my experience of all the good and bad that expat life in Moscow entails.

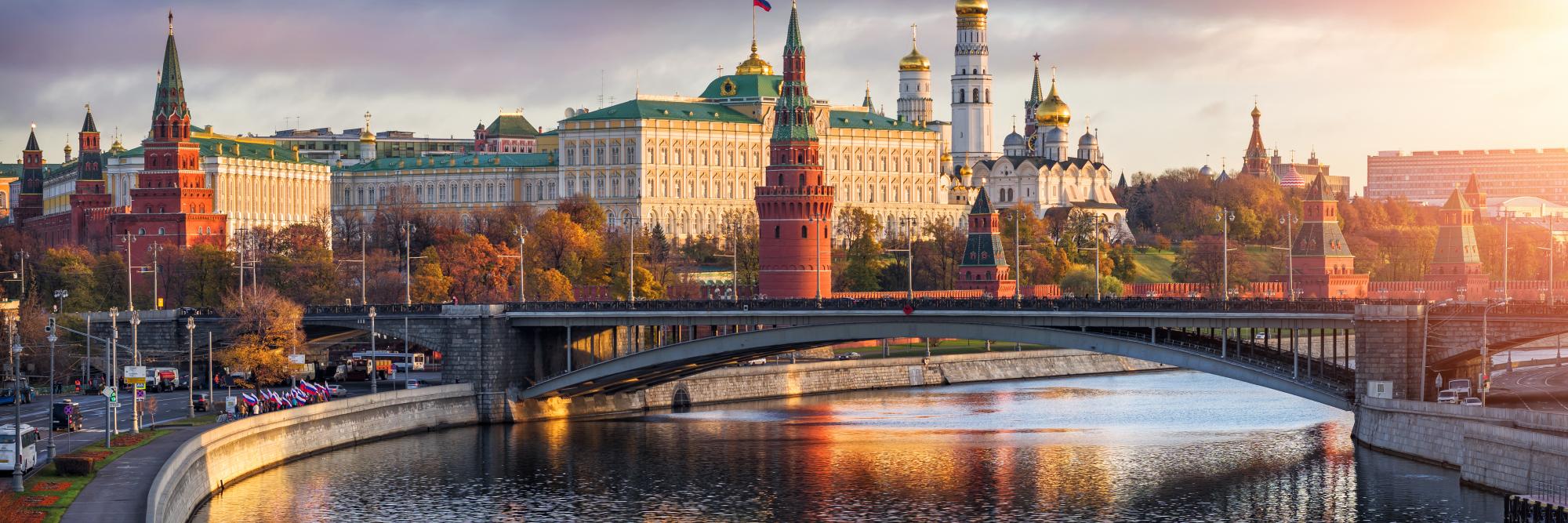

Firstly, let's look at Moscow itself. There's an energy to this city that is quite unlike anywhere else I've ever seen. The hustle and bustle of Moscow's metro during rush hour, for example, cannot fail to get your heart racing. It is vibrant, intense and also beautiful. On the other hand, its raw energy and power can crush you underfoot if you don't treat it with the respect it deserves and commands. The Moscow metro, like so much of Moscow, manages to be appealing and repellent at the same time. But either way, it cannot fail to make an impression. You either love or hate Moscow, and sometimes feel both emotions at the same time, but you cannot ignore it. It is never dull.

In terms of architecture, the city has much to offer. The Kremlin is one of these few sights that look as imposing in reality as they do on TV. To give an idea of its size, I sometimes walk around it on my way home from work and it takes about an hour. Red Square is impressive even without the red army tanks, GUM must be the world's most opulent department store and its location on Red Square cannot be rivalled.

Other sights you're sure to recognize are the Bolshoi, the White House, Stalin's magnificent Seven Sisters skyscrapers, the Neva river, Gorky Park and so on and so forth. There are also more museums than I can count and a string of beautiful historic towns around Moscow in the Golden Ring. So, in terms of tourist attractions, Moscow may not rival Paris or Rome, but it would take far longer than the year I spent here to see everything. And, of course, that's only the beginning. Beyond Moscow, there's St. Petersburg, Siberia and all the rest of this enormous continent of a country.

But let's return to Moscow. As I have already mentioned, it is a truly enormous city, and that always lends a certain life to a place. The population is heading towards 10 million, and if the Russian government made it easier to obtain residence permits to live here, there would be a lot more. Abroad, Russians have a reputation for sloth and indolence, but when you see 'Mighty Moscow' in action, you can recognize that for the falsehood it is. Moscow's wide boulevards, its teeming streets, its 6-lane highways are all in a desperate rush to get somewhere. Where everyone is heading to and why they are in such a hurry, I have no idea.

As to the Muscovites themselves, they are a race of survivors. Even a cursory look at this Russia's history shows us that life here is seldom easy. In Soviet times, you had to fight a queue for a simple loaf of bread. Now the stakes are much higher, but you still need to fight. If you're lucky, cunning or well connected you might become very rich very quickly, but it's more likely you'll have to fight to get by. This is not a country for the faint hearted.

Perhaps I am going too far. I don't want to give you the impression that Moscow is a land of hardened cutthroat criminals ready to sell their own mother for a bottle of vodka. There is already far too much of this mafia hype in the western press. What I am trying to explain is why the average Russian acts so differently to the average American. The Russian man or woman in the street does not smile unless he is happy, he does not engage complete strangers in meaningless conversation, he does not suffer fools gladly. Indeed, there is a Russian proverb that perhaps sums it up - "Only a fool smiles all the time." However, while Russians can appear unfriendly and rude, when you get to know them, you will find that they are considerate, helpful and well…friendly. I suppose the Russian concept of friendship is much deeper and less superficial than friendship elsewhere.

However, if you are reading this, you're probably a teacher thinking about coming to work here, so I should start to concentrate on that. I was a Director of Studies (DoS) for a company called BKC-IH. It's the largest language school in Russia and an affiliate of the International House network. Indeed, it may be the largest language school in all of Eastern Europe. To give you some idea of the size of the school, there are about 180 teachers -100 or more work exclusively for the company on full time contracts and about another 80 do some hours for BKC on a freelance basis. BKC has many locations - there are six large central schools and many more smaller satellite schools. The other really big language schools are Language Link and English First. If you’re particularly well qualified and experienced, you’d be better off trying the British Council, which offers much better terms and conditions than other language schools.

During my telephone interview, I was encouraged to apply for a senior position because of my qualifications (DELTA) and length of experience (6 years full-time EFL teaching). To be honest, I had never considered the possibility of a senior position before. I had always imagined senior staff to be almost 'a race apart' and possessing magical organizational powers that mere mortal teachers could not hope to imitate. However, when the position of ADOS was offered to me, I found it hard to say no. Opportunities like that, I reasoned, do not come along every day. Approximately five months afterwards, BKC promoted me to DoS, the position I currently hold. The company has also paid for me to an International House Young learner course, and sent me to DoS training course at International House London. I think it is fair to say that for me at least, BKC-IH was quite a career rocket. In other words, there are many opportunities for teachers in Russia.

I am not saying, of course, that every teacher who goes here will have the same positive experience. Indeed, many teachers at BKC and the other language schools do not enjoy their time in Moscow and seem to start counting down the days until the end of their contract almost from the day they arrive. In general, teachers who feel like this are new to teaching and to living abroad. Perhaps they arrive with unrealistic expectations of what teaching life is like. In order to try and create a realistic picture of life in Moscow, let me briefly describe what awaits you.

Accommodation

When you arrive at the airport you will be met by a Russian member of staff and taken to your flat. Central Moscow is ridiculously expensive, so all flats are in the suburbs. By Russian standards, the flats are quite nice. However, by American or British standards, they could be considered a little basic. Most flats do not have a television and many flats do not even have washing machines, for example. Two teachers have to share each two-bedroomed flat, so apart from the kitchen, there is very little communal space. Fortunately, I'm married so this wasn’t really an issue. Moreover, teachers spend most of the day away from their flat. The flats themselves are clean and furnished and just about any student in the world will have lived in a lot worse.

Work

I have always believed that EFL teaching is by far the best job in the world. What other job would pay you to travel the world getting to know foreigners and not even require you to learn their language? Moreover, the students who attend language academies tend to be very educated, liberal and very interested in you, your language and your culture.

However, like everything else in life, it is not a bed of roses. Firstly, split shifts are an unfortunate fact of life for most teachers. Moreover, in a city the size of Moscow, travel time also eats into your day. Furthermore, Russian students often spend a third of their monthly income on their English classes, so they expect you to know what you're talking about. In other words, preparation is essential and will further eat into your free time. On the other hand, preparation for class is not wasted time. The more time you spend preparing, the better a teacher you will become and the quantity of time needed for preparation will decrease as your experience increases. Here lies another beauty of EFL teaching - we are being paid for jobs while we are still learning how to do them. I can't think of another profession in the world that allows you to do that!

Social life

In Moscow, the social life you lead is limited only by your wallet and your social skills. While Moscow is by no means a cheap city, it is possible to have a good time here relatively cheaply, once you find out where to go.

There is also an enormous variety of nightlife on offer. On the other hand, Russians do not have a bar/cafe culture and tend to entertain friends at home. As a result of this, in the suburban areas where you'll be living, it will be hard to find a 'local'.

Safety

While Moscow is not the safest city in the world it is by no means the most dangerous either. If you exercise caution and don't mark yourself out as an easy target, then you'll be unlucky to have anything happen to you.

Police

What I dislike most about Moscow is the police force. In fact, the Russians often refer to them by their slang name – 'rubbish'. While it is not as vivid as the English term 'pig', it somehow describes them more accurately. Perhaps I'm being unfair here. I'm sure the majority of them are honest, hard working professionals, but there are a sizeable minority who are corrupt, violent and dangerous. While I have not had any real trouble with them myself (apart from having to bribe an obese malodorous border guard while on the way to Estonia on a visa run), several other teachers have had. While nothing really serious has happened, I have taken the advice of teachers who have been here a lot longer and now I never speak English out loud when there is a policeman near, and I always look like I know where I'm going. Fortunately, these two procedures will also stop the criminal fraternity from noticing you too.

I suspect that the more cynical readers among you will conclude that the words of a DoS are inherently biased and not to be trusted. However, I feel I have given you an honest 'warts and all' description of life in Moscow and the school I worked for.